We have discussed setting off interrupting words and phrases with commas. Today, we will talk about when to set off adjective clauses with commas — and when not to.

We have discussed setting off interrupting words and phrases with commas. Today, we will talk about when to set off adjective clauses with commas — and when not to.

First, what is a clause? A clause is a group of words, sort of like a phrase, but a clause has a subject and a verb. In fact, independent clauses are simple sentences, so we won’t be talking about those because sentences don’t interrupt other sentences. However, dependent, or subordinate, clauses are not complete sentences. There are a few different types of dependent clauses; today we are talking about adjective clauses.

What is an adjective clauses? Well, it isn’t called an adjective clause because it contains an adjective, although it can. It is called an adjective clause because the entire clause acts like an adjective, modifying a noun (or sometimes a pronoun). Adjective clauses never begin sentences. They are either in the middle or at the end of a sentence.

All adjective clauses begin with one of the following five words: which, that, who, whom, or whose. Here are examples of sentences using each of these words to begin an adjective clause:

- The cookies on the table, which are slightly burned, are for the bake sale. (subject: which/verb: are/modifies: cookies on the table)

- The cookies that are on the table are for the bake sale. (subject: that/verb: are/ modifies: cookies)

- The girl who is at the end of the line is my cousin. (subject: who/ verb:is/modifies: girl)

- The teachers whom I remember best were the stricter ones. (subject:I/verb: remember/modifies: teachers )

- That tall kid, whose name is similar to mine, is in all my classes. (subject: name/verb: is/modifies: kid)

In all of the above examples, the clause is interrupting the sentence. (If you leave out the clause, you still have a complete sentence.) However, the clause can end the sentence, as in these examples:

- Those are the cookies that I baked last night.

- That is the girl whom I am asking to the prom.

- This is my favorite book, which I have read six times!

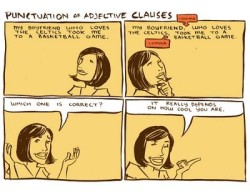

Notice that in some of the sentences the clause is set off with commas, and in others it is not. The “rule”

is the same as for interrupting phrases. If you need the clause to define what you are talking about, you do not use commas. If the clause is additional information, or a “by the way,” use commas. Sometimes you can also put the clause in parentheses or even enclose it in dashes instead of using a comma . . . but this post is about commas.

Clauses that are necessary for the meaning of the sentence are called restrictive. They restrict the noun being described, so the reader knows which one. Restrictive clauses are not set off with commas. Clauses that add information that is not really necessary for the meaning of the sentence are called nonrestrictive. They don’t serve to limit the noun they modify; use commas around them.

Look at the first five examples above. In the first sentence we already know the sentence is about the cookies on the table and that they are for the bake sale, The fact that they are burned is additional information. In the second sentence we need the clause to tell us which cookies the sentence is talking about — the cookies on the table.

In the third sentence, we wouldn’t know which girl was your cousin without the clause that tells us which girl — the girl at the end of the line. In the fourth sentence, which teachers were the stricter ones? The ones you remember best.

In the last example, you identify that tall kid, so the reader knows whom you are talking about. The fact that his or her name is similar to yours is additional information.

Can you use pausing as a clue? If you would pause, use commas; if you wouldn’t pause, don’t use a comma. This technique is pretty accurate most of the time, but it is best to know the WHY.

Why use a clause at all? Why not just say “The girl at the end of the line is my cousin”? You can. I am not telling you how to write, or whether to use a phrase or a clause. But when you use a clause, know when to use commas and when not to.

Finally, when do you use which? that? who? whom? whose?

Which is used for things, not people, and usually in nonrestrictive clauses (with commas).

That is used for things and usually in restrictive clauses (without commas).

Who is used for people and is the subject of the clause.

Whom is used for people and is the object in a clause.

Whose is used for people and is possessive.

Who, whom, and whose are used for both restrictive and nonrestrictive clauses.

Sometimes you can use that for people, especially for groups of people: That is the tribe that lives in North Dakota.

———————————————————

What’s new with the Grammar Diva?

Here is my interview on BlogTalk radio with Sharon Michaels.

Here in my interview on KRCB’s A Novel Idea.

My books are for sale — along with other books by local authors and beautiful works of art– at the Healdsburg Center for the Arts Holiday Gift Gallery, 130 Plaza Street in Healdsburg.

I will be on the panel discussing all kinds of editing and its important at the December meeting of the Bay Area Independent Publishing Association.

Fifty Shades of Grammar: Scintillating and Saucy Sentences, Syntax, and Semantics from The Grammar Diva is now available! Makes a great gift!

Leave a Reply