It is my pleasure to present this guest post by Audrey Kalman.

Audrey Kalman is the author of the novels The Last Storyteller, What Remains Unsaid, and Dance of Souls, as well as the collection Tiny Shoes Dancing (shortlisted for the 2019 International Rubery Book Award). Her short fiction and poetry have appeared in more than a dozen print and online journals. She co-teaches the Birth Your Truest Story workshop series (more at http://www.birthyourtrueststory.com), offers editing and coaching services for writers, and is at work on another novel. Find out more at her website.

——————————————————————————————–

Lost in Translation

…or obscured by transcription, adrift in adaptation, concealed by rendition

By Audrey Kalman

I took French in seventh grade. My rural junior high school offered a choice between that or German. Thus began my romance with French—although French may seem less romantic once you learn it derives from Vulgar Latin (which simply means spoken, non-Classical Latin). I dreamed of traveling to Paris. Failing that, I dreamed of a handsome French exchange student coming to live with us. I even created a French-inspired pen name: Cecile Marchand, a mash-up of my middle name and the French word for “merchant.” I took French through college, becoming proficient enough to read Camus, Sartre, and Flaubert in the original and get around on a trip to France after I graduated.

Then I never spoke it again.

My South American boyfriend attempted to teach me Spanish in my mid twenties, but by then French was imprinted in my brain as “the other language” of this native English speaker. I had to keep stopping to think, gracias or merci? hola or bonjour? It didn’t help that he teased me about my accent. I never achieved anything close to Spanish fluency, which I regretted when my kids were little sponges and everyone touted the benefits of getting an early start on a second language.

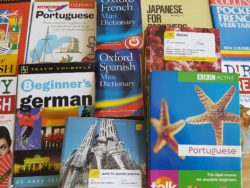

So today I am at the mercy of translators, not only for Spanish but for any of the world’s 7,000 or so other non-English languages.

It’s hard enough to get our words right even when we’re speaking the same language. We talk past each other. We say one thing and the listener hears something else. Or we outright say what we don’t mean. Layer onto this same-language communication challenge the task of, say, being a diplomat charged with ratcheting down an armed conflict, and suddenly the tremendous burden on the translator becomes obvious. Many a book and movie plot has hinged on a translator slyly shifting the speaker’s words to change the course of history. And there are real-world examples of diplomatic mistranslation.

The subtleties of translation play out in smaller, less dramatic ways. Recently, I’ve been closely reading and analyzing short stories, some written originally in Russian and Chinese. As I examine how each phrase stirs me as a reader, I have a niggling question: Is this exactly how the phrase would strike me as a native speaker? Probably not. For example, a new translation of Felix Salton’s 1922 book Bambi, a Life in the Forest, which became the basis of the popular Disney movie based on its first translation, was translated afresh. The new translator, Jack Zipes, told Publisher’s Weekly he was shocked at the book’s dystopian vision, a story, he said, that “was never intended for children.”

Inspired by thinking about translation, I returned to my dog-eared college copy of Michel Déon’s Les gens de la nuit (The People of the Night). I could still understand the first sentences without benefit of translation: “This past year,” the book begins, “I stopped sleeping. I couldn’t have said why.” To check my comprehension, I typed them into Google Translate, which returned, “That year, I stopped sleeping. I couldn’t confess why.” To my ear, “confess” sounds wrong in this context. But do I really know, as a college-level French speaker who abandoned the language for decades, exactly which English words Déon would have chosen?

Language, it turns out, is not just language. Sure, it consists of words, phrases, sentences, and paragraphs put together by rules of grammar and syntax. But language comes with culture and history baked in. When we speak, history echoes. Concepts foreign to a culture often have no words in that culture.

So, on the translator’s shoulders falls not only the need to know words but the necessity of putting down stepping stones the reader can cross to understanding, conveying not only the meaning of individual words but the weight, intention, and nuance behind them.

Sometimes I think these dedicated wordsmiths may be the bridge builders holding our fragile world together.

Oh, thanks so much for this article! I so enjoyed it, from the ‘dream of going to France’ to the ‘keeping the fragile world together’. I am left with the question for myself, “How will I apply this to my life?”

Thanks so much for the comment!

Maybe just having a greater awareness of it is application enough. Thanks for reading!

Not just translators, interpreters too☺

Yes! Thanks for the reminder.

Indeed and of course too. And you’re welcome👍